Because the best things in life are free

|

|

|

For those new to GNU/Linux and Free/Libre Open Source Software (OSS or FLOSS) and the associated communities, some explanations may be in order. How to be part of this community, how to find your way and how to make things work for you. This article starts with several aspects of the OSS community and OSS development, indicating what makes OSS developers tick. Then it explains how to deal with problems. The novice Linux user is invited to exchange the more common troubleshooting reflex (retry, reboot, reinstall) with a more OSS minded method (check, communicate, correct). The last section provides some more concrete starting points for those who want to learn more about their Linux system. For those who want to skip the background explanation and directly go to that last part, just click here. However, knowing a bit more about the background may help you to understand why supporting the Free Software / Open Source Community will benefit yourself.

A well respected professional programmer, who had written a driver for an ethernet card, was asked why he would devote his spare time to write this driver and then give away the code under the GNU General Public License (GPL). The point the inquiring person tried to make was that this programmer must be crazy, doing a professional job and giving away the code. His answer (well, paraphrased anyway): "I put in a few evenings of work, and in return I get an 80MB Operating System for free, including the source code, and you're telling me I'm the one who's crazy??"

Basically, to develop code as OSS means that developers can work together to create software that is much more powerful and capable than they could have created alone, and the GPL ensures that they will always have access to any further improvements of their code. So if you want to fill a need, the GPL is a great way to get others to contribute to your code; they too will forever be able to profit from their own work.

The FLOSS development shows strong contrast with closed source or proprietary software development, that in most cases is just a means to an end: namely to generate the highest possible income and to ensure the ability to do just that in the future. One company very good at that is Microsoft. But this article is not about proprietary solutions, so I'll save that criticism for some other time.

The point I would like to get across is the following: OSS developers are giving the fruits of their efforts away for free, for all to use. Most of them do not get paid for their efforts, or at least, not by you. They often do aim to make their program the best it can be. So your complaints may not always be welcome, but your bugreports (especially of reproduceable bugs) very often are.

Many of the difficulties and problems that people encounter when starting out with Linux are due to being unfamiliar with the system. In other words, the problem is not with the system, but with the user. This is sometimes referred to as 'operator error'. If things don't behave as you, as a novice Linux user, expect or would wish, that doesn't mean they are wrong - even if it means that you may take a bit longer to get used to things. The standard system behaviour is well thought out, and the complexity and flexibility of the whole implies by definition that there is much to learn. One example: logging in graphically as root is not a good thing. You are free to educate yourself as to the how and why. The Mandrake developers have made it more difficult (but not impossible) in Mandrake 9.1 to log on graphically as root. Kudos to Mandrake for trying to get people on the right path, this is a Great Thing (tm). You can still log on graphically as root (it is Linux, remember) - but don't complain if it's not so straightforward to do, and definitely don't complain if, due to this, at some point you end up with a broken system. So if the system doesn't behave as you think it should, don't complain, but figure out why it does behave that way. This being said, it is clear that many pieces of software, OSS or not, have bugs. I will not contradict that you can easily run into some of these bugs, instead I want to explain how to deal with bugs and other problems with Open Source Software. The 'other system' troubleshooting paradigm mainly consists of the Three R's:

Many novice Linux users still suffer from this paradigm, as some observation on some mailinglists or forums will easily show: "I even rebooted..." or worse: "I reinstalled the whole machine, twice... ". Also, replies to people with problems along the lines of: "yeah, well, you should use another distribution / window manager / desktop manager" are often due to this wrong mentality. I'd now like to present the OSS troubleshooting paradigm, which I like to sum up with the following Three C's:

Check whether your problem is not just an operator error, which is very often the case: due to unfamiliarity with the system the user falsely expects it to behave differently than how it was designed. These errors were (I do hope my speaking in the past tense is correct in this case; at least it should be) often answered with: RTFM (Read The Friendly Manual) or UTFS (Use The Friendly Search) (note that I prefer to use another f-word than is usually aimed at in these acronyms). Your check should start at the manual page or documentation, and can include any or all of the following: acquaintances who have experience with the program at hand, the project website, google, newsgroups and forums.

Communicate to see if others (possibly including the developers of the software in question) are having or are observing the same problem. If they have, see how they managed to solve it, or at least work around it. It may be that you have come across a bug that cannot be fixed directly. Again, you may use any or all of the following: newsgroups, project mailinglist, forums. As a last point in this process, you can correct the problem on your own system (either because you've just found out it was an operator error, or fix it as per the feedback you got in the former step) and / or the developers of the software can and should correct the problem by fixing the source code, in which case a next pointrelease (or for the more daring and experienced users: the CVS code, which is the code under development) will include the fix. With proper application of the Three C's, OSS continuously gets improved, and you get rewarded for your effort: in the next version of that certain program your problem will have been fixed. Also, please realise that if there is a persistant bug that you have trouble with but apparently doesn't get fixed, and you didn't follow the Three C's, you have no-one but yourself to blame. You may consider this one of the costs of OSS. One of the great things of OSS is that the source code is freely available, so you don't depend on those few developers of one specific software vendor who fix bugs, and if the root cause is found you don't have to wait for the next big release. Agreed, this applies more to expert users. But in any case, and best of all, you don't ever have to pay for that next release in which your problem is solved.

To get started on learning how to use your shiny new Operating System, I'd like to propose the following: whenever you get stuck or feel the need for some more information, read the documentation that came with your system. Yeah, I know it's a real shocker, but few people actually ever pay attention to that. For instance, in Mandrake you go from the start-button to Documentation, then select the Howtos. Many programs also have their own built in documentation. KDE and Gnome, the two major Desktop Environments, both have excellent online help files. In Gnome, go from 'start' (the footprint) to 'help' which starts 'Yelp'. In KDE, all KDE applications have a help entry on the menu at the top, where you can select '[Application] Handbook'. OpenOffice.org is another group of programs with extensive online documentation.

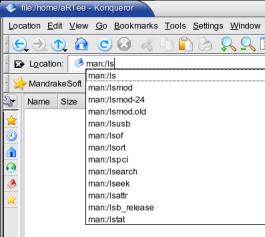

You may also use Konqueror (KDE's multipurpose filebrowser) to read manual pages (manpages) for commands and programs. If you are using KDE, click the 'home' icon on your taskbar (panel) or desktop. Then, in the location field (where it says:

just enter man:/[command] Or, even simpler, if you are browsing this page with Konqueror (yes it is also a webbrowser, with the same engine as Mac OS X's Safari, KHTML), you can click the above link. Note that even if you are using Gnome, you can do this as long as Konqueror is properly installed. Of course you have to substitute [command] for the command or program you would like more information about. If you don't enter a [command], Konqueror will take you to the main index. Note a neat feature of Konqueror when you start typing your [command] -- Konqueror shows the remaining possibilities in the drop down part.

Those who prefer the Command Line Interface (CLI) can of course also read the manpages by entering man [command]into any terminal window. I know that for people who are not familiar with manpages, they come across as cryptic, mostly due to their scientific format, but after getting used to them, one quickly realises manpages are a very welcome and powerful part of the GNU/Linux system and software. An alternative that is generally considered easier to read for the novice, but which may not be available for a program you want to know more about, are the info pages. In Konqueror: info:/[command] or on the command line: info [command]will get you plenty of information about the use of certain commands and programs. To find out more, you can also read books, magazines and websites, search the web, newsgroups and forums. And most of all, if you get stuck, remember the Three C's.

Note that I use the terms Free Software and Open Source Software to denote the same thing, and I don't want to go into the differences of these terms from a philosophical standpoint. The term 'Free Software' stresses the fact that the code is free in the sense that the user can do with it as he/she pleases, but it's somewhat confusing since it can still be charged for. 'Open Source Software' stresses the fact that the source code is available, but from the term it is not clear that the user can do with it whatever he/she wants. 'FLOSS (Free/Libre Open Source Software)' leaves less doubt but also requires some explanation and is a bit long... Maybe 'Freedom Software' (what 'libre' actually hints at) should be used...

|